By JORDAN RAU

Amid all the turbulence over the future of the Affordable Care Act, one facet continues unchanged: President Trump’s administration is penalizing more than half the nation’s hospitals for having too many patients return within a month.

Medicare is punishing 2,573 hospitals, just two dozen short of what it did last year under former President Obama, according to federal records released Aug. 2. Starting in October, the federal government will cut those hospitals’ payments by as much as 3 percent for a year.

Medicare docked all but 174 of those hospitals last year as well. The $564 million that the government projects to save also is roughly the same as it was last year under Obama.

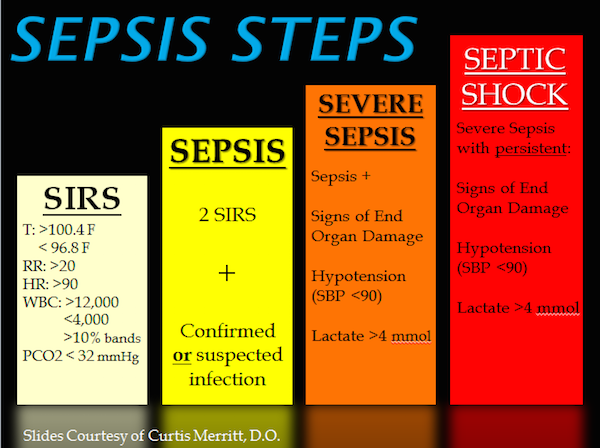

High rates of readmissions have been a safety concern for decades, with one in five Medicare patients historically ending up back in the hospital within 30 days. In 2011, 3.3 million adults returned to the hospital, running up medical costs estimated at $41 billion, according to the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The penalties, which begin their sixth year in October, have coincided with a nationwide decrease in hospital repeat patients. Between 2007 and 2015, the frequency of readmissions for conditions targeted by Medicare dropped from 21.5 percent to 17.8 percent, with the majority of the decrease occurring shortly after the health law passed in 2010, according to a study last year in the New England Journal of Medicine conducted by Obama administration health-policy experts.

Some hospitals began giving impoverished patients free medications that they prescribe for their recovery, while others sent nurses to check up on patients seen as most likely to relapse in their homes. Readmissions dropped more quickly at hospitals potentially subject to the penalty than at other hospitals, another study found.

“The sum of the evidence really suggests that this program is helping people,” said Dr. Susannah Bernheim, the director of quality measurement at the Yale/Yale-New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, which measures readmission rates for Medicare.

But the pace of these reductions has been leveling off in the past few years, indicating that the penalties’ ability to induce improvements may be waning.

“Presumably, hospitals made substantial changes during the implementation period but could not sustain such a high rate of reductions in the long term,” the New England Journal article said.

An analysis by Bernheim’s group found no decrease in the overall rate of readmissions between 2012 and 2015, although small drops in the medical conditions targeted by the penalties continued.

“We have indeed reached the limits of what changes in how we deliver care will allow us to do,” said Nancy Foster, vice president for quality at the American Hospital Association. “We can’t prevent every readmission. It could be that there is further room for improvement, but we just don’t know what the technique is to make that happen.”

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program was created through a section of the ACA designed to use the purchasing power of Medicare to reward hospitals for higher quality. Those penalties, along with other ones aimed at improving hospital care, have been spared the partisan rancor over the law, and they would have continued under the GOP repeal proposals that stalled in Congress. But they have also been largely ignored.

Dr. Ashish Jha, a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said the fight over abolishing the Affordable Care Act has drowned out talk about how to make the health care system more effective. “We’ve spent the last six months fighting about how we’re going to pay for health insurance, which is one part of the ACA,” he said. “There’s been almost no discussion of the underlying health care delivery system changes that the ACA ushered in, and that is more important in the long run to be discussing because that’s what’s going to determine the underlying costs and outcomes of the health system.”

The readmission penalties are intended to neutralize an unintended incentive in how Medicare pays hospitals that had profited from return patients. Medicare pays hospitals a lump sum for a patient’s stay based on the nature of the admission and other factors. Since hospitals generally are not paid extra if patients remain longer, they seek to discharge patients as soon as is medically feasible. If the patient ends up back in the hospital, it becomes a financial benefit as the hospital is paid for that second stay, filling a bed that would not have generated income if the patient had remained there continuously.

Because of how the readmission-penalty program was designed, it is not surprising that the new results are so similar to last year’s. As before, Medicare determined the penalties based on readmissions of the same six types of patients: those admitted for heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic lung disease, hip or knee replacements or coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Hospitals were judged on patients discharged between July 2013 and June 2016. Because the government looks at a three-year period, two of those years were also examined in determining last year’s penalties.

This year, the average penalty will be 0.73 percent of each payment Medicare makes for a patient between Oct. 1 and Sept. 30, 2018, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis. That too was practically the same as last year. Forty-eight hospitals received the maximum punishment of a 3 percent reduction. Medicare did not release hospital-specific estimates for how much lost money these penalties would translate to.

More than 1,500 hospitals were exempted from penalties this year as required by law. Those include hospitals treating veterans, children and psychiatric patients. Critical access hospitals, which Medicare also pays differently because they are the only hospitals in their areas, were excluded. So were Maryland hospitals because Congress has given that state extra leeway in how it distributes Medicare money.

Of the 3,241 hospitals whose readmissions were evaluated, Medicare penalized four out of five, KHN’s analysis found. That is because the program’s methods are not very forgiving: A hospital can be penalized even if it has higher than expected readmission rates for only one of the six conditions that are targeted. Every non-excluded hospital in Delaware and West Virginia will have their reimbursements reduced. Ninety percent or more will be punished in Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York and Virginia. Sixty percent or fewer will be penalized in Colorado, Kansas, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, South Dakota and Utah.

Since the readmission program’s structure is set by law, the administration cannot make major changes unilaterally, even if it wanted to.

Congress last year instructed Medicare to make one future alteration in response to complaints from safety-net hospitals and major academic medical centers.

They have objected that their patients tended to be lower income than other hospitals and were more likely to return to the hospital, sometimes because they didn’t have a primary care doctor and other times because they could not afford the right medication or diet. Those hospitals argued that this was a disadvantage for them since Medicare bases its readmission targets on industry-wide trends and that it hurt them financially, depriving them of resources they could use to help those same patients.

Bernheim noted that despite those complaints, safety-net hospitals have shown some of the greatest drops in readmission rates. In October 2018, Medicare will begin basing the penalties on how hospitals compared to their peer groups with similar numbers of poor patients. Akin Demehin, director of policy at the hospital association, said, “We expect the adjustment will provide some relief for safety-net hospitals.”

Medicare is planning to release two other rounds of recurring quality incentives for hospitals later this year. One gives out bonuses and penalties based on a mix of measures, with Medicare redistributing $1.9 billion based on how hospitals perform and improve. The other, the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program, cuts payments to roughly 750 hospitals with the highest rates of infections and other patient injuries by 1 percent.