By LISA GILLESPIE

Christian Hospital says its costly difference of opinion with Medicare hinges on how to count the large number of poor people that the St. Louis hospital treats.

Medicare penalizes hospitals that readmit too many patients within 30 days of discharge, and Christian expects to lose almost $600,000 in reimbursements this year, hospital officials said. Christian is one of 14 hospitals in the BJC HealthCare System.

Steven Lipstein, chief executive of BJC, which includes Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, said Medicare doesn’t play fair because its formula for setting penalties does not factor in patients with socioeconomic disadvantages — low-income, poor health habits and chronic illnesses for instance — that contribute to repeated hospitalizations.

If Medicare did that, Christian’s penalty would have been $140,000, Lipstein said.

As every hospital executive knows, half a million dollars pays for “a whole lot of nurses.”

In total, hospitals around the country lost $420 million last year under Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, an initiative of the federal health law that seeks to push hospitals to deliver better patient care.

Since the program began in 2012, “recent trends in readmissions suggest that (it) is having the desired impact,” Health Affairs reported in January.

Hospitals have lobbied Congress and Medicare to change the rules and gained some ground May 18 when Rep. Patrick Tiberi, R-Ohio, introduced a bill in the House to adjust Medicare’s program to account for socioeconomic status. The bill was co-sponsored by Rep. Jim McDermott, D.-Wash.

Meanwhile, the Missouri Hospital Association is trying to pull public opinion behind it.

This year, the association overhauled its consumer Web site, Focus On Hospitals, to include not only the federal readmissions data, but also each member’s readmissions statistics, adjusted for patients’ Medicaid status and neighborhood poverty rates.

The federal government already adjusts its readmissions data for age, past medical history and other diseases or conditions, and that’s public on Medicare’s Hospital Compare Web site.

The association explains its adjustment methodology in an article on the site. “There is emerging national research that suggest poverty and other community factors increase the likelihood a patient will have an unplanned admission to the hospital within 30 days of discharge,” it states.

The hospital group’s alternative data — Lipstein’s source for how Christian could have reduced its 2015 penalty — comes from a study it commissioned. One finding: Missouri hospitals’ readmissions rates improved by 43 to 88 percent when patients’ poverty levels were considered.

“The question is, has [readjustment] been done in a just and fair way,” Lipstein said. The Missouri Hospital Association “has provided methodology that suggests what the Feds are doing is unfair.”

The controversy over penalties is likely to grow beyond the readmissions question. Federal health officials have announced that they want to shift from paying doctors and hospitals based on the services they provide and move toward a value-based system that encourages a better quality of care and better outcomes while controlling costs.

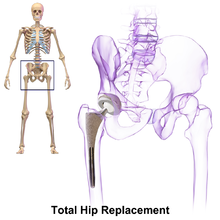

Medicare bases penalties on readmissions on the care of Medicare patients who were originally hospitalized for one of these five conditions — heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic lung problems and elective hip or knee replacements.

This year, Medicare penalized almost half of all hospitals — 2,592 to be exact — for excessive readmissions. More than 500 were fined 1 percent of their Medicare payments, or more, for the fiscal year that will end Sept. 30.

Still, the system harms so-called safety-net hospitals most, said Herb Kuhn, the Missouri Hospital Association’s president.

“Hospitals in difficult neighborhoods are getting worse scores, and those in affluent [ones] are getting better. It’s time to adjust [rates] for the disease of poverty,” he said.

Kuhn’s experience makes him an influential voice on health-policy issues. He was deputy administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services from 2006 to 2009 and before that, director of the agency’s Center for Medicare Management. In April, Kuhn completed a three-year term on the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which advises Congress.

The commission proposed an alternative to Medicare’s readmission penalties last year. Others are also studying modifications.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has taken a cautious stance, but last year CMS announced it is working with the National Quality Forum, a nonprofit group whose research influences CMS’s quality metrics, on a trial to test socioeconomic risk adjustment.

But Leah Binder, CEO of the Leapfrog Group, a nonprofit patient safety group, says Medicare’s readmission penalties have pushed hospitals to improve care and adjusting the data for patients’ poverty levels could deter them.

“Hospitals are paid a lot of money. I think they can find a way to handle their readmissions, the way they should have been handling them all along,” Binder said.