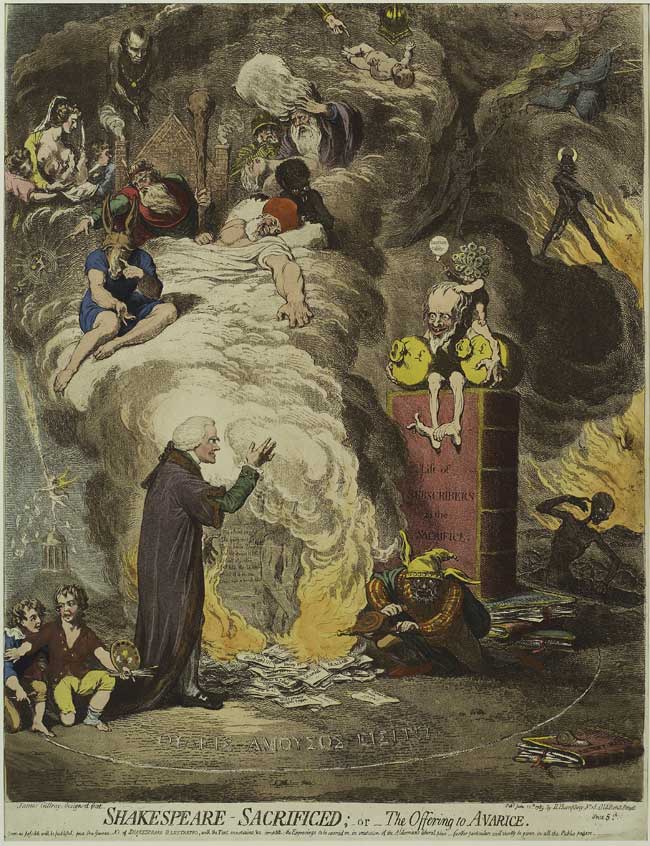

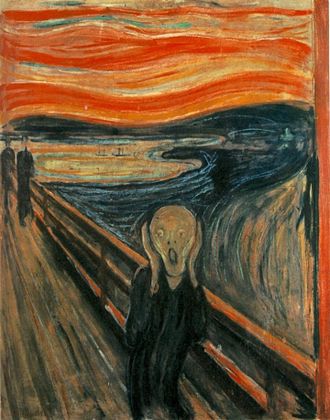

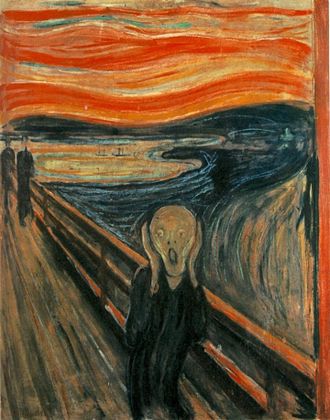

“The Scream,” by Edvard Munch.

By JORDAN RAU

For Kaiser Health News

Andrea Schankman’s three-year relationship with her insurer, Coventry Health Care of Missouri, has been contentious, with disputes over what treatments it would pay for. Nonetheless, like other Missourians, Schankman was unnerved to receive a notice from Coventry last month informing her that her policy was not being offered in 2017.

With her specialists spread across different health systems in St. Louis, Schankman, a 64-year-old art consultant and interior designer, said she fears that she may not be able to keep them all, given the shrinking offerings on Missouri’s health-insurance marketplace. In addition to Aetna, which owns Coventry, paring back its policies, UnitedHealthcare is abandoning the market. The doctor and hospital networks for the remaining insurers will not be revealed until the enrollment period for people buying individual insurance begins Nov. 1.

“We’re all sitting waiting to see what they’re going to offer,” said Schankman, who lives in the village of Westwood. “A lot of [insurance] companies are just gone. It’s such a rush-rush-rush no one can possibly know they’re getting the right policy for themselves.”

Doctor and hospital switching has become a recurring scramble as consumers on the individual market find it difficult or impossible to stay on their same plans amid rising premiums and a revolving door of carriers willing to sell policies. The instability, which preceded the health law, is intensifying in the fourth year of the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces for people buying insurance directly instead of through an employer.

“In 2017, just because of all the carrier exits, there are going to be more people making involuntary changes,” said Katherine Hempstead, a senior adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a New Jersey philanthropy. “I would imagine all things being equal, more people are going to be disappointed this year versus last year.”

Forty-three percent of returning consumers to the federal government’s online exchange, healthcare.gov, switched policies last year. Some were forced to when insurers stopped offering their plans while others sought out cheaper policies. In doing so, consumers saved an average of $42 a month on premiums, according to the government’s analysis. But avoiding higher premiums has cost many patients their choice of doctors.

Jim Berry, who runs an Internet directory of accountants with his wife, switched last year from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Georgia to Humana after Blue Cross proposed a 16 percent premium hike.

Despite paying Humana $1,141 in premiums for the couple, Berry, who lives in Marietta, a suburb of Atlanta, said they were unable to find a doctor in the network taking new patients. They ended up signing up with a concierge practice that accepts their insurance but also charges them a $2,700 annual membership, a fee he pays out of pocket. Nonetheless, he said he has been satisfied with the policy.

But last month Humana, which is withdrawing from 88 percent of the counties it sold plans in this year, told Berry his policy was not continuing, and he is unsure what choices he will have and how much more they will cost.

“It’s not like if I don’t want to buy Humana or Blue Cross, I have five other people competing for my business,” Berry said. “It just seems like it’s a lot of money every year for what is just basic insurance, basic health care. I understand what you’re paying for is the unknown — that heart attack or stroke — but I don’t know where the break point is.”

To be sure, the same economic forces — cancelled policies, higher premiums and restrictive networks — have been agitating the markets for employer-provided insurance for years. But there is more scrutiny on the individual market, born of the turmoil of the Affordable Care Act.

Dr. Patrick Romano, a professor of medicine at the University of California at Davis Health System in Sacramento, Calif., said the topic has been coming up in focus groups he has been convening about the state insurance marketplace, Covered California. Switching doctors, he said, “is a disruption and can lead to interruptions in medications.”

“Some of it is unintentional because people can have delays getting in” to see their new doctor, he said. “Some of it may be because the new physician isn’t comfortable with the medication the previous physician prescribed.”

Dr. John Meigs, an Alabama physician and president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that whatever the source of insurance, changing doctors disrupts the trust a patient has built with a physician and the knowledge a doctor has about how each patient responds to illnesses. “Not everything is captured in a health record” that can be passed to the next doctor, Meigs said.

There is little research about whether switching doctors leads to worse outcomes, said Dr. Thomas Yackel, a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. In some cases, he said, it can offer unexpected benefits: “Having a fresh set of eyes on you as a patient, is that really always a bad thing?”

With the shake-up in the insurance market, access to some top medical systems may be further limited. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee, which has included the elite Vanderbilt University Medical Center in its network, is pulling out of the individual marketplace in the state’s three largest metro areas: Nashville, Memphis and Knoxville. Bobby Huffaker, CEO of American Exchange, an insurance firm in Tennessee, said so far, no other carrier includes Vanderbilt in its network in the individual market.

In St. Louis, Emily Bremer, an insurance broker, said only two insurers will be offering plans next year through healthcare.gov. Cigna’s network includes BJC HealthCare and an affiliated physicians’ group, while Anthem provides access to other major hospital systems, including Mercy, but excludes BJC and its preeminent academic medical center Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

“These networks have little or no overlap,” she said. “It means severing a lot of old relationships. I have clients who have doctors across multiple networks who are freaking out.”

Aetna said it will still offer policies off the healthcare.gov exchange. Those are harder to afford as the federal government does not provide subsidies, and Aetna has not revealed what its networks will be. In an e-mail message, an Aetna spokesman said the insurer was offering those policies to preserve its option to return to the exchanges in future years; if Aetna had completely stopped selling individual policies, it would be banned from the market for five years under federal rules.

Even before St. Louis’ insurance options shrunk, Bremer said she had to put members of some families on separate policies in order for everyone to keep their physicians. That can cost the families more, because their combined deductibles and maximum out-of-pocket payments can be higher than for a single policy, she said.

“Every year our plan disappears,” said Kurt Whaley, a 49-year-old draftsman in O’Fallon, Mo., near St. Louis. After one change, he said, “I got to keep my primary-care physician, but my kids lost their doctors. I had to change doctors for my wife. It took away some of the hospitals we could get into.”

Brad Morrison, a retired warehouse manager in Quincy, Ill., said he has stuck with Coventry despite premium increases — he now pays $709 a month, up from $474 — because the policy has been the cheapest that would let him keep his doctor. “That’s the one thing I insisted on,” he said. “I love the guy.”

With Coventry leaving the Illinois exchanges, Morrison is unsure whether his alternatives will include his physician. His bright spot is that he turns 65 next spring. “I’m trying to hold out until I get to Medicare,” he said.