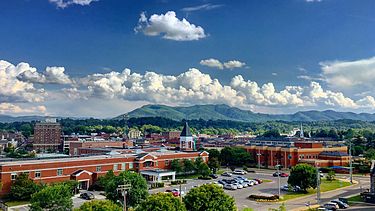

Downtown Johnson City.

By PHIL GALEWITZ

JOHNSON CITY, Tenn.

Looking out a fourth-floor window of his hospital system’s headquarters, Alan Levine can see the Appalachian Mountains, which have long defined this hardscrabble region.

What gets the CEO’s attention, though, is neither the steep hills in the distance nor one of his Mountain States Health Alliance hospitals across the parking lot. Rather, it’s a nearby shopping center where his main rival — Wellmont Health System, which owns seven area hospitals — runs an urgent-care and outpatient cancer center. Mountain States offers the same services just up the road.

“Money is being wasted,” Levine said, noting that duplication of medical services is common throughout northeastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia, where Mountain States and Wellmont have been in a healthcare “arms race” for years, each trying to out duel the other for the doctors and services that will bring in business.

The companies now want to merge, which would create a monopoly on hospital care in a 13-county region that studies have placed among the nation’s least healthy places. The merger’s savings would pay for a range of public-health services that they can’t afford now, the companies project. And they are trying to pull it off without Washington regulators’ approval, breaking with hospitals’ usual path to consolidation.

In a typical case, a plan that eliminates so much competition in a market would almost certainly provoke a court battle with the Federal Trade Commission, which enforces antitrust laws and challenges anti-competitive behavior in the health industry.

To avert such a fight, the hospitals are using an obscure legal maneuver available in Tennessee and Virginia and some other states.

Generally known as a Certificate of Public Agreement (COPA), the process works like this: If regulators in Virginia and Tennessee agree that the merger is in the public interest, Wellmont and Mountain States would operate as one company under a state-supervised agreement governing key parts of their operations, including setting prices. The states’ approval would prevent the FTC from challenging the merger under federal antitrust law.

Their decisions could come as soon as this month.

In exchange for approval, Mountain States and Wellmont promise to use money saved from the merger to offer mental-health and addiction-treatment services and attack public-health concerns, such as obesity and smoking — areas previously neglected by the systems that don’t increase hospital admissions and bring in big revenue, hospital officials said

“The question that needs to be asked is whether tight state oversight of a monopoly is better than failed competition,” said Robert Berenson, a health-policy expert at the Urban Institute.

Little-Used And Rarely Challenged Mechanism

The federal antitrust exemption made possible under a COPA dates to a Supreme Court ruling in the 1940s used only about a dozen times to allow hospital mergers. One was an hour away from here, in Asheville, N.C.

There’s little scholarly research on COPAs’ results.

Last summer, the FTC dropped its challenge to a merger of two West Virginia hospitals after the state adopted a COPA law and permitted the deal.

In recent years, hospital mergers and acquisitions have created behemoth health systems that have used their status to demand high payments from insurers and patients. Studies by health economists have repeatedly found that consolidation means higher prices.

But the same calculus may not apply here and in other regions where a preponderance of patients are poor or uninsured, officials from both Mountain States and Wellmont say.

While President Trump and Republicans in Congress stress the value of free-market principles in healthcare, officials of both hospitals argue that in their part of Appalachia the market has led to unnecessary spending, driven up health costs and forced them to focus on services that produce the highest profits rather than meet the community’s most pressing health needs. In this deeply conservative region, where death rates from cancer and heart disease are among the nation’s highest, the hospitals say only a state-sanctioned monopoly can help them control rising prices and improve their population’s health.

Without their proposed merger, Levine said, both hospital systems would likely have to sell to an out-of-market chain. That would likely eliminate local control of the facilities and could lead to massive layoffs and the closure of hospitals and services, he said. Together, the two hospital systems employ about 17,000 people.

The FTC, which is urging the states to reject the hospitals’ plan, contends the hospitals could form an alliance or take other steps short of a merger to accomplish the benefits they say one will bring. The agency says the hospitals’ market probably would be no worse off if one chain merged with a company outside the area.

Feds Wary Of Promises

The hospitals are making big promises to sell their deal. They say no hospitals would close for at least five years, although some could be converted to specialized health facilities to treat problems such as mental illness or drug addiction. After the merger, all qualified doctors would have staff privileges at all hospitals to treat patients. No insurer would pay lower rates than others. The new hospital system would spend at least $160 million over 10 years to improve public health, expand medical research and support graduate medical education for work in rural areas.

The FTC maintains that the hospitals’ pledges are unreliable and dismissed them as having “significant shortcomings, gaps and ambiguities” in an analysis filed with state regulators in January.

Levine said the plan is the best deal for the community given the factors that handicap the hospitals. Those include declining populations and Medicare reimbursement rates that are lower here than other parts of the country because of lower average wages. Another concern is the cost of caring for uninsured people — neither Virginia nor Tennessee expanded Medicaid under the health law, which would have lowered uninsured rates.

“Competition is and should be the first choice, but in an area where competition becomes irrational and there are limited choices, there has to be a Plan B. If not this, then what?” he said.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Tennessee, the state’s largest health insurer, is not opposing the hospitals’ combination, a spokesman said. But its counterpart in Virginia, Anthem, hasn’t been persuaded.

“Anthem does not believe that there are any commitments that will protect Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee healthcare consumers from the negative impact of a state-sanctioned monopoly,” the company said in a statement.

Wanted: Better Job Prospects

The proposed COPA has strong support among large employers in the region, including Eastman, a Kingsport, Tenn., chemical company with $9 billion in annual revenue that employs more than 7,000 people locally. “We get local governance, input and control … and that’s a lot better situation for us,” said David Golden, a senior vice president at Eastman.

Still, walking around Johnson City — the region’s largest city, with almost 67,000 people — it’s easy to feel an unease among small employers and residents about a merger. Many worry about possible job cuts.

“Eliminating duplication of services means eliminating people,” said Dick Nelson, 60, who runs a coffee and art shop downtown and has lived here for 27 years. “I don’t care how much health care costs because my insurance will pay it,” he said.

In Kingsport, where Wellmont and Mountain States each has a hospital, Thorp is leery about a merger, too. “It’s an economic move, not an enhancement of medical care,” said Thorp, who runs a newsstand downtown. “We pride ourselves here for having good education and health care. They say there won’t be any services or jobs cut, but if that’s the case then what’s the point of the merger?”

Levine said no place better supports the case for a hospital merger than Wise County in southwestern Virginia, a scenic area with about 40,000 people whose three hospitals all operate below half their capacity. Mountain States and Wellmont each own a hospital in Norton, the county seat, with 4,000 residents. Despite few patients, the hospitals still bear hard-to-cut costs for buildings, equipment and adequate staffing levels, Levine said.

On a recent weekday morning, Lonesome Pine Hospital, a Wellmont facility in Big Stone Gap, Va., looked nearly deserted. No volunteers or staffers were visible inside its main entrance and fewer than a fifth of its 70 acute-care beds were being used.

A five-minute drive away, Mountain States’ Norton Community Hospital’s 129 beds are about a quarter filled. Its maternity unit delivers fewer than five babies a week. The hospital offers hyperbaric oxygen therapy — a treatment that pays well under Medicare’s reimbursement rates — to help diabetics heal their wounds. But it has no endocrinologists to help diabetics manage their disease to avoid such complications. Despite a high rate of heart disease in the community, there’s no cardiologist on staff.

Whether a state-sanctioned merger will resolve the incongruities — here or in other poor regions — depends on how firmly regulators hold the hospitals to their pre-merger commitments. If the merger plan gets rejected, Mountain States and Wellmont will resume arch-competitive business practices that do not always put community interests first, said Bart Hove, Wellmont’s CEO.

“It’s about competing for the dollar in any way you can and extracting a dollar from your competition,” Hove said. “You do what you can to drive patients to your hospital.”